Editor’s note: The below contains spoilers for The Sandman.

Neil Gaiman has always liked to put a little nasty in with the nice. In fact, he has made a career out of character-driven, surrealistic storytelling, and it’s one of the most prominent aspects of his writing style. So it comes as no surprise that the Netflix version of his immensely popular comic book series The Sandman has a collection of characters that have distinct flaws to go with their flair. It’s his way of humanizing them and making them more relatable. They aren’t Marvel superheroes. There’s no Captain America or Thor in this bunch. His group of characters has shortcomings just like the rest of us. The British author’s penchant for creating characters that reside within this realm of moral ambiguity is a device that he uses with great aplomb. And it is within this space that we most often find our shared traits. His proclivity for musings about our commonalities with an ethereal god-like Morpheus or the tragic, supremely defective mortal John Dee make his tales uniquely engaging.

Tom Sturridge (Irma Vep, Far from the Maddening Crowd) and his portrayal of the titular character, for instance, prove to be a tough nut to crack. There are obvious similarities between him and Mr. Wednesday from one of Gaiman’s most popular books, American Gods. While it’s clear that they both have overarching intentions that are benevolent and in the interest of protecting their mortal subjects, there are instances in almost every episode when you will find yourself asking, “Wait, this is our good guy? Is he even a good guy?” It’s certainly understandable that after being caught by a spell cast by the bumbling, amateurish wizard Roderick Burgess (Charles Dance) and imprisoned in a glass case for 105 years, the mercurial dream king might be just a little ticked-off and hell-bent on reclaiming his seat as the King of Dreams. However, his brooding and quiet intensity isn’t terribly endearing as a main character.

Demeaning and disrespectful exchanges with his ever-loyal assistant Lucienne (Vivienne Acheampong) who dutifully held down the dream realm during his stead in captivity make it hard to get your Morpheus pom-poms out and may remind some of us of our own bosses in real life whose unwarranted hubris and ire can make our daily lives hell. And the repeated narcissistic, petulant phraseology of, “Not even I can do that!” doesn’t fill you with the warm fuzzies for our anti-hero. So you mean there are things that you can’t do? Now you’re starting to remind us of that kid in high school that couldn’t figure out why nobody wanted to hang with them. Even Morpheus knows that he can rub gods and mortals alike the wrong way when he grants a man the gift of immortality with whom he meets every 1000 years. It later becomes evident that he granted this wish simply to have a companion, someone to talk to. Apparently, even gods get lonely. Nevertheless, Gaiman’s gambit with his audience is that his god is far from perfect, and then he dares you to outweigh his shortcomings with the overall goodness of his intentions. Essentially, do the means justify the end?

Like a child in the sandbox who can’t find his buried toys, Morpheus goes about searching for his essential tools which consist of a small bag of sand, his elephantine helm, and a powerful ruby stone. Along the way, we’re introduced to several more characters that have all too common problems that make them more empathetic. Johanna Constantine (Jenna Coleman), a necromancer and occultist for hire who, in the process of retrieving Morpheus’ bag of sand, must deal with the awkward conclusion of a romantic relationship, and John Dee (David Thewlis), a particularly tragic character that you will find at the center of almost every good Neil Gaiman yarn. His use of meek, misunderstood mortals is a device he’s used before and is incredibly relatable. The son of Ethel Cripps (Joely Richardson), the woman who initially stole the ruby, John is the most human of all the characters in The Sandman. Broken, abandoned by a mother who shelved him away in mental institutions for most of his life, he is a lost soul, searching for purpose and change. He’s been lied to his entire life and after being gifted the powerful ruby that makes dreams come true, John does what a lot of us would do in the same position. Tired of being surrounded by false pretenses and untruths, he wishes for a world with more honesty. That doesn’t sound at all bad, much less malicious, but with his broken mind having changed the true power of the stone, the well-paced diner episode reveals that his wishes end up hurting more than helping. No good deed goes unpunished as Gaiman reminds us that too much honesty is problematic. Maybe all the little “white lies” we tell aren’t always such a bad thing, right?

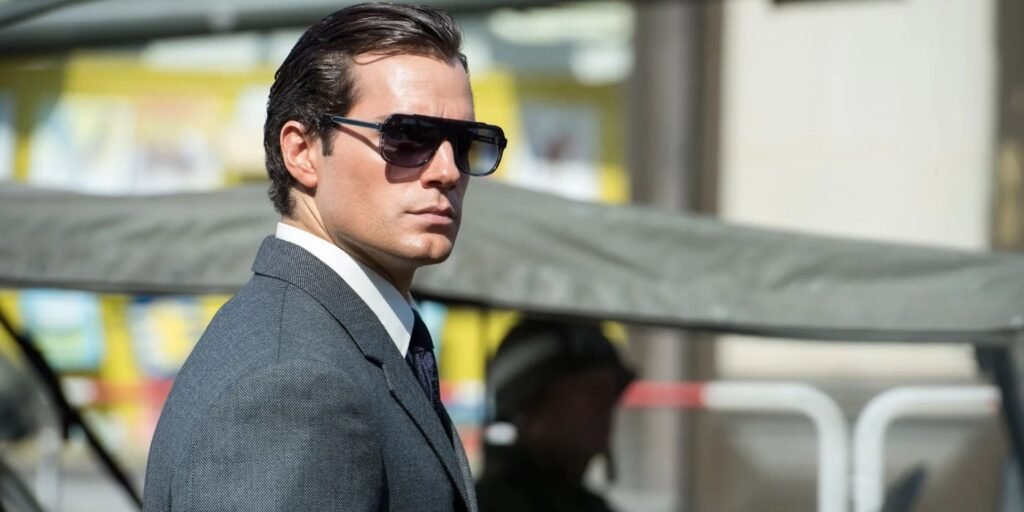

Sure, there are completely lovely and compassionate characters like the young dream vortex Rose Walker (Kyo Ra), who represents the good in man and redemptive core qualities that we seek to embody and find easy to root for, as well as the most horribly flawed of them all, the smooth-talking missing nightmare The Corinthian (Boyd Holbrook), whose cruelty is only surpassed by his taste for eyeballs. But with these representations being largely sensationalized and offsetting one another, it’s the area in between these two poles that Gaiman’s The Sandman will challenge the audience to find the things we like about his creations. Ironically, he recently opened up about how it was initially a challenge to develop well-rounded, relatable characters, “I didn’t really get characters. I didn’t understand what characters were. And it took a while for me to learn really how to write good characters, characters who were three-dimensional, characters who felt real, characters who felt real to me.”

Ultimately, in the tenth and penultimate episode, Morpheus lets go of his greatest flaws, his stubbornness, and his arrogance. Heeding the wisdom of his sister and easily the most likable of the Morpheus’ three siblings, Death (Kirby Howell-Baptiste), Dream realizes that they exist to serve humans and that one cannot exist without the other. “Our purpose is our function.” Death says. It’s hard to find flaw with that. Now what to do about Desire (Mason Alexander Park)?